In the Riverfront Bar & Grill of Marietta Ohio’s century-old Lafayette Hotel on a recent steamy night, the chatter intensified with an air of excitement. Friends were calling friends to get updates on the Queen of the Mississippi, a giant paddle wheel boat that was expected to slide alongside the hotel any minute, right outside the window.

It was awkward for me, a 47-year journalist, captured by the excitement of a luxury river cruise ship, while typing notes from a conversation a few hours earlier, downriver in Belpre, population 6,500.

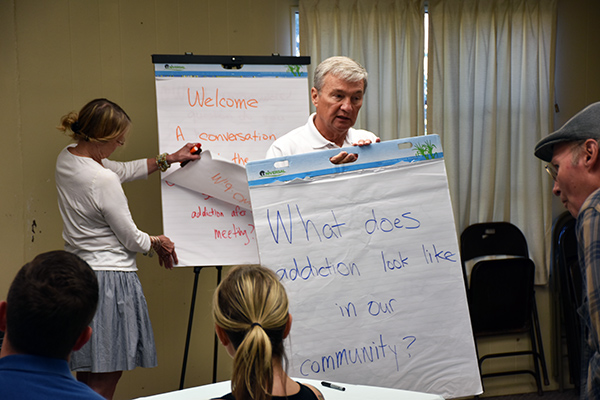

The conversation? About 40 people had gathered to talk about the opioid crisis killing 5,000 a year in Ohio and West Virginia. There were tears as mothers related stories of children. Belpre, clearly, had not escaped the scourge. Nor had Parkersburg, W.Va., where we had been the night before, and Marietta, where we would hold a community meeting the following night.

There already had been 11 of these meetings across Ohio as part of the Your Voice Ohio project, a collaborative of more than 40 news outlets trying to gain a better understanding of the people we serve. At the invitation of the What’s Next Mid-Ohio Valley organization and local media, Your Voice Ohio bridged the Ohio River for this one weekend.

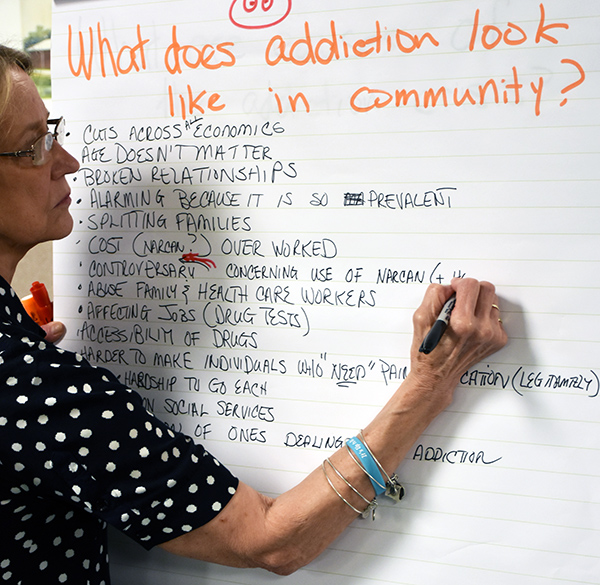

There were many consistencies in the Mid-Ohio Valley — or MOV as the people of Parkersburg-Marietta call themselves. Like all of Ohio, they agreed that there are families and children in crisis; a need for complex, extensive treatment, early preventative education and a need to change the stigma of addiction; and treatment instead of arrest.

But MOV meetings offered something not heard as clearly across the rest of Ohio: A convincing belief that they had been exploited.

“Is this a valid finding?” was the question posed to Aaron Payne, a reporter for WOUB at Ohio University. He covers issues in the valley for a National Public Radio collaborative that stretches the length of the Ohio River. Yes, he said, when you consider the history of the coal industry, which extracted wealth from the valley then left communities without jobs. The same question was asked of a group of local retired professors, public officials, engineers and business owners at the Lafayette Hotel breakfast room the next morning. They looked at the foolish old journalist, nodded yes, then moved on to Donald Trump’s meeting with Vladimir Putin, which was occurring as they sipped coffee.

The 150 folks who gathered over three days put exploitation and the drug crisis in perspective. The pharmaceutical industry and medical community offered a pill to ease the pain of a spiritual hole caused by plummeting income, no jobs and nowhere to go.

And, people said in every meeting, no one is immune to the destruction of lives evolving from the high-powered opioids.

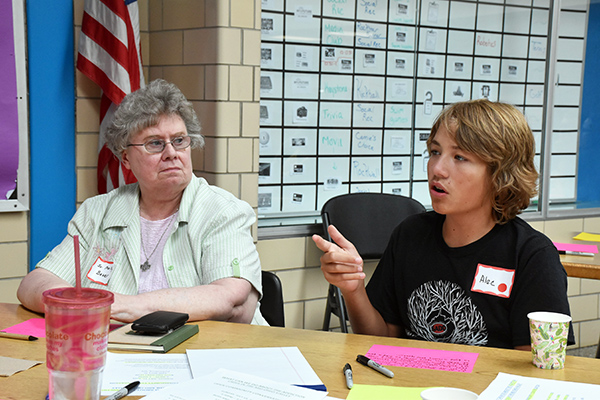

One retiree came to the Belpre session and confessed before the start that she knew nothing about the crisis and came because she was curious. As she moved from table to table, she offered several “Oh-my” responses. “This is really complicated, and solutions won’t be easy,” she said at the end.

She moved from a thought at the beginning — “Maybe if people would just go to church” — to a laundry list of actions.

The MOV meetings illustrated the vast disconnect between people in the heartland and their state governments in Charleston and Columbus and policy makers in Washington.

The same week we met in the Ohio Valley, the White House announced an initiative to obtain pledges from employers to hire people.

The reality, said one of the men at the Lafayette hotel, is that there are “Help wanted” signs all along the road from the northeast corner of Ohio to the Ohio River. But those jobs are unfilled, said the people in the meetings, because people in recovery often accumulated a record of felony arrests so they could buy drugs. Even though they’re clean, they can’t get hired.

So, while politicians win pledges for jobs and job training, there is little benefit to the thousands of people in recovery who can’t get hired and pull families back together because of a criminal record.

What else did we learn about disconnect? One person in recovery said addicts reach a point of despair that creates a rare moment for intervention. There needs to be a public hotline that gets them whisked to services.

People in the recovery business quickly said, “There IS a number,” and offered it up.

Right, said the man in recovery. “Did you ever try to call it?”

Here’s what he said happens: The desperate caller receives a list of phone numbers and instructions. Think about that. A person who has hit rock bottom, perhaps at 2 a.m., staring at life-threatening withdrawal in the next several hours, must make phone calls hoping someone will answer and have an opening for an appointment. And then, transportation?

For politicians and people in the recovery business, the hotline works. But what about the those struggling with addiction?

A doctor in one meeting said drug intervention in the schools is a necessity. He said the average age of first exposure in the Marietta area is about 13 or 14. There is evidence that delaying experimentation just two years significantly reduces the chances of experimenting with drugs at all, he said.

But a high school student said there is something wrong with the mandatory drug programs that already exist. Students go to an assembly to hear a speaker and instead tune to their cell phones. The education, the student said, must be calculated. In other communities, we heard citizens say that education must start as early as kindergarten, and it must be education on coping skills to help children make good decisions in bad situations — not drug education.

As I dragged my suitcase past the display cases of weapons, paddle boats and ballcaps at the Lafayette, the coffee bunch was there for the thrice-weekly meeting. They were reflecting on the failures of government. Outside, another paddle wheel had come to shore, tourists were climbing the hill to tour historic Marietta and locals in lawn chairs were sitting under trees to watch the excitement. One local hinted that it was an escape from current politics.

Interesting place, this MOV. They’ve seen jobs disappear, incomes plunge and watched loved ones die. And they are convinced they’ve been exploited. The question arises: What if a feeling of exploitation becomes pervasive across the country? Maybe it has, only people elsewhere aren’t as quick to reckon with it?

What’s refreshing in the MOV is that after the last meeting, people spilled into the parking lot and lingered awhile. There were hugs, and on a note card, one person wrote: “I learned how much our community cares about each other and the future of our community. WE all can and are willing to fix this.”