Your Voice Ohio has listened to over a thousand Ohioans as they talked about the challenges facing their communities and what they see as solutions. Throughout our community dialogues concerning the addiction crisis, a common observation made was that when drugs were primarily considered an issue that plagued black communities, Ohio responded by building prisons and locking up thousands of young black men. But when the opioid crisis killed a disproportionate number of white Americans, suddenly Ohio had sentencing reform and had reframed addiction as a health issue.

Those were tough words for which people in the room had little to say. It’s no secret this country and this state has problems. The racial motivations behind the war on drugs are well documented; and it’s the state of Ohio where “stop-and-frisk” searches, which were generally conducted on minorities, was originally ruled constitutional in Terry v. Ohio.

Even in more recent years, Ohio has among the highest number of reported race-based crimes in the country. In 2015, Ohio was one of just two states (along with California) reporting more than 300 race, ethnicity or ancestry-based hate crimes.

An overarching lesson from all of our community conversations is that if we are to restore trust in local news, we must reflect in our reporting that we are listening. By addressing Ohioans top issues in the way they describe them, and by generating discussion about solutions, we can demonstrate that we want to be not only a meaningful resource for the community but also a part of the solution to the challenges they face.

As we move through the process of connecting with stakeholders and designing future conversations with members of the community, it’s important to take a step back, reflect, and ask ourselves: How may our own news coverage affect racial bias within our community?

Racial Perceptions of Crime

A report by the Sentencing Project released in 2014, synthesizes existing research showing the skewed racial perceptions of crime. The report found that “white Americans, who constitute a majority of policymakers, criminal justice practitioners, the media, and the general public, overestimate the proportion of crime committed by people of color and the proportion of racial minorities who commit crime”. It is true that racial minorities commit certain crimes at higher rates than whites, but research shows that whites overestimate these differences, attributing an exaggerated amount to people of color. A national survey conducted in 2010 asked white respondents to estimate the percentage of burglaries, illegal drug sales, and juvenile crime committed by African Americans. The researchers found that the respondents overestimated actual black participation in these crimes – measured by arrests – by approximately 20 to 30 percent.

Why do these overestimations matter?

Historically, when people believe that those who commit crime are similar to them, they are more likely to reflect on the underlying circumstances of the crime and respond with empathy and mercy. However, when

individuals perceive a racial gap between themselves and those who commit a crime, there is a tendency to react not with compassion, but with anger. Attributing crime to racial minorities limits empathy toward offenders and encourages retribution as the primary response to crime. The proof of this is out there; studies have shown that white Americans who more strongly associate crime with people of color are more likely to support punitive criminal justice policies.

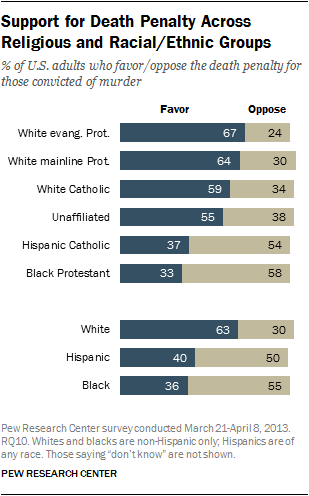

A 2013 Pew Research Center survey found that while the majority of whites supported the death penalty for someone convicted of murder (63% supported, 30% opposed), blacks and Hispanics were more likely to oppose rather than support this punishment (with only 36% of blacks and 40% of Hispanics supporting).

This tendency of white Americans to support greater punitiveness for people of color is especially striking when taking into account that whites are actually far less likely than blacks and Hispanics to be victims of crime. In 2008, according to the Bureau of Justice, African Americans were 78% more likely than whites to experience household burglary and 133% more likely to experience motor vehicle theft. Hispanics were also 46% more likely than non-Hispanics to be victims of property crimes.

Researchers have shown that the public’s racial perceptions of crime go hand-in-hand with support for punitive crime policy, to which elected officials, prosecutors, and judges have been very responsive. Consequently, although whites experience less crime than people of color, they are more punitive.

What role does the news media play? – “If it bleeds, it leads.”

In a study by the Berkeley Media Studies Group at the Public Health Institute, it was found that 76% of the public say they form their opinions about crime from what they see or read in the news. In a Los Angeles Times poll, 80% of respondents stated that the media’s coverage of violent crime had increased their personal fear of being a victim. These survey results are consistent with communications research findings that the news media largely determines what issues we collectively think about, how we think about them, and what kinds of policy alternatives are considered viable.

Given this clear reliance on the media for knowledge on crime and crime policies, there can be dire consequences to how news media decides to frame coverage and chooses which stories are reported. Unfortunately, researchers have shown that crime reporting tends to exaggerate crime rates, exhibits both quantitative and qualitative racial biases, and is not “systemically aware“.

“If it bleeds, it leads,” goes the saying about local news coverage. But not all spilled blood gets an equal amount of attention. Although there is certainly a range of media coverage about crime, with reporters who are cautious not to promote biased public perceptions, less mindful coverage is common. Because of the media’s historical gravitation toward notable crimes, upticks in news media coverage of crime doesn’t always correlate with broader crime trends. Unfortunately, this kind of coverage results in more than just increase the public fear of becoming a victim, it also distorts the public’s sense of who commits crime. By over-representing whites as victims of crimes perpetrated by people of color, crime news delivers a double blow to white audiences’ potential for empathetic understanding of racial minorities.

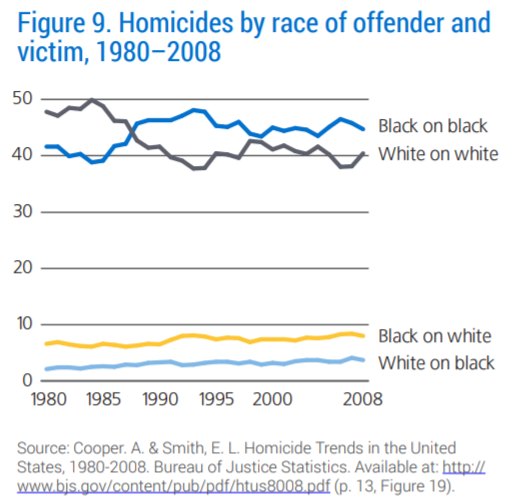

In an analysis by the Bureau of Justice Statistics, for example, one can see that Homicide is overwhelmingly an intra-racial crime involving men. But media accounts often portray a world over represented by black, male offenders and white, female victims.

One study of a Columbus, Ohio major newspaper reported on the city’s murders – which were predominantly committed by and against black men – examined whether unusual or typical cases were considered “newsworthy”. The researcher found that journalists gravitated to unusual cases when selecting victims (white women) and to typical cases when selecting perpetrators (black men). Researchers have found similar selection bias in coverage of Hispanic suspects and non-Hispanic victims on television news.

A study in Los Angeles found that 37% of the suspects portrayed on television news stories about crime were black, although blacks made up only 21% of those arrested in the city. Another study found that whites represented 43% of homicide victims in the local news, but only 13% of homicide victims in crime reports. And while only 10% of victims in crime reports were whites who had been victimized by blacks, these crimes made up 42% of televised cases. These disparities a prevalent across the country and are greatest when the victim’s race is taken into consideration.

There are also more subtle racial differences in crime coverage. A study of television news found that black crime suspects were shown in more threatening contexts than whites. Black and Latino suspects were also more often presented in a non-individualized way than whites – by being referred to in generalized threatening terms rather than by name – and were more likely to be shown as threatening – by being depicted in physical custody of police. Huffington Post has a collection of headlines regarding white suspects virus headlines regarding black victims that demonstrates the issue well.

Remedies & Recommendations

Journalists can draw on proven interventions to reduce racial misconceptions of crime, and news producers can monitor and correct for disparities in reporting, using the recommendations (pp. 27-36) from the Center for Children’s Law and Policy as a starting point. These recommendations include expanding sources beyond criminal justice professionals, contextualizing crime within broader underlying social problems, providing in-depth coverage of more typical crimes rather than highlighting anomalous ones, and auditing content to compare coverage with regional crime trends. Further recommendations as described by the Sentencing Project include:

Reduce racial disparities in crime coverage

By measuring and tracking the racial composition of offenders and victims in crime news and comparing these with regional crime rates, news producers can improve the representativeness of their coverage. More nuanced attention is also needed to improve how – not just how much – crime reporting differs by race. Content analysis can help to identify racial disparities in the extent to which suspects are presented in non-individualized and threatening ways.

Contextualize sentencing and crime stories

By reporting on criminal sentences that are representative, and documenting their lifelong consequences, news producers can help to educate the public about the reality of existing penalties. By contextualizing specific crime stories or policy debates within crime trends, they can avoid creating the impression of a false crisis. Correctly reporting on crime trends in part requires recognizing the difference between the Department of Justice’s two crime measures: the Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Program and the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS).

The UCR measures crimes reported to the police – which are affected by changes in victim reporting and police categorization practices – as well as arrests – which are heavily influenced by law enforcement practices. The NCVS measures crime victimization regardless of whether incidents were reported to or cleared by the police. The two data sources sometimes depict conflicting trends. Noting these nuances and accurately reporting levels of crime and sentencing would help both policymakers and the public develop more informed views about crime policies.

Recognize implicit racial bias

In their comprehensive review of implicit racial bias research, the Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity concludes that “education efforts aimed at raising awareness about implicit bias can help debias individuals.” Dispelling the illusion that we are colorblind in our decision making is a crucial first step to mitigating the impact of implicit racial bias. Mock jury studies have shown that increasing the salience of race in cases reduces bias in outcomes by making jurors more conscious of and thoughtful about their biases.

Further Reading:

- A journalist should step correct:’ Building trust in local news, Columbia Journalism Review

- 5 ways to bring different voices into your stories, Poynter

- Diversity & Inclusivity in Journalism, American Press Institute

- Diversify Your News Coverage, Journalism Education Association